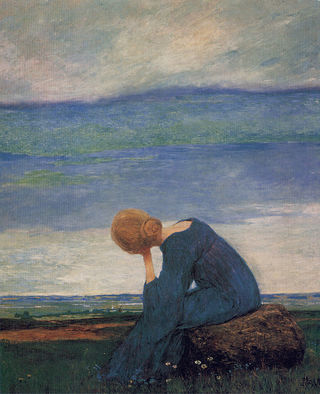

A Place of Longing

Let me begin our Advent journey with a question: What do you long for? I am not asking what you want for Christmas. I’m asking what you long for in the depths of your heart and soul? What is missing from your life?

If you’re like the folks at worship yesterday, you said things like: peace (personal and communal), safety, forgiveness, wholeness, acceptance, empathy, healing, reconciliation, bridging of the divide in our world.

The themes of Advent - hope, peace, joy and love – are born more from the longing for them than from actually having them. As I consider what I long for today, it is also what I hope for. And, while I’m a pretty hopeful person in general, there are times (especially lately) when I feel my hope needs to be bolstered and fortified by the hope of others. Part of me wants to isolate and crawl into a hole when I’m feeling down, distressed and less than hopeful. Yet, when I witness hopeful actions and attitudes of others, my own hope brightens. And, I desperately don’t want to lose hope for the world, for a better future, for light to conquer the darkness.

Maria Popova, who writes the Marginalian, said,

Hope — and the wise, effective action that can spring from it — is the counterweight to the heavy sense of our own fragility. It is a continual negotiation between optimism and despair, a continual negation of cynicism and naivete’. We hope precisely because we are aware that terrible outcomes are always possible and often probable, but that the choices we make can impact the outcomes.

Hope gets wheels moving, feet walking, voices speaking… hope and longing is the impetus to positive change. To understand how this deep longing connects to the birth of Jesus, we need to back up.

In seminary I learned something called historical-critical context. It means delving into the historical setting of a Biblical passage – political, social, economic, religious setting – so that you can better understand the people, the situation, the purpose and intent of the passage, etc.

For example, it would make no sense to give a presentation on Mahatma Gandhi as a Hindu saint without talking about British imperialism in India and all that meant for the people of India. It would make no sense to talk about Malala Yousafzai as the youngest Nobel Peace Prize laureate for her fight for girls right to be educated without knowing what the Taliban had been doing to the people, and especially girls, of Pakistan.

The same goes for Jesus. It makes no sense to talk about the story of his birth and life without understanding the role that Rome played in the story. Have you ever wondered why Luke begins the birth narrative of Jesus by placing it within the context of a census (Luke 2:1-3)? Especially when:

- there is NO historical evidence of a census of the whole Roman world,

- Quirinius was not the governor of Syria until 6 CE and historians and scholars place Jesus’ birth in the time of Herod the Great which ended years before that,

- and when there was a census taken, people were counted where they lived, worked and paid their taxes, and it was a crime not to be at home when you were counted. No one was traveling back to their place of birth… that would have been a bureaucratic nightmare and logistical impossibility.

So, if we can’t take the passage literally, we need to ask why it started with:

In those days, Caesar Augustus published a decree ordering a census of the whole Roman world. This first census took place while Quirinius was governor of Syria. All the people were instructed to go back to the towns of their birth to register.

Clearly this was important framing for the author of Luke. Let me unpack it briefly

First… The census serves to get Joseph and Mary to Bethlehem which fulfills the prophecy in Micah 5:2 that a great ruler would come from Bethlehem. For the people then, this was symbolic language for saying that Jesus was the “son of David,” the ideal king. Jesus was, as Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan wrote in The First Christmas, “the fulfillment of God’s promise to Israel and Israel’s deepest yearning – for a king like the great king David, for a different kind of life and a different kind of world, for light in the darkness, for the presence of God with us.”

Second… this passage serves to place the event of Jesus’ birth within the larger framework of Rome. His birth didn’t just affect the people of a small backwater town, it had much bigger ramifications.

Third… Luke is being clear about the power structure of the day. The people of those days knew (and so did not need to be told in the scripture) Caesar Augustus was hailed as God, Son of God, Lord, Savior of the World (by the way, Augustus in Latin means “One Who Is Divine”). As a dictator, Caesar clearly had military, economic and political power.

Jesus couldn’t compete with the military, economic and political power of Rome, but he could compete when it came to ideological power. So that is exactly what Luke does. Luke’s birth narrative has the angels proclaiming that a Savior, the Messiah, was born. We see here the foreshadowing of a confrontation between the lordship of Caesar and the lordship of Jesus. There is a very clear juxtaposition between the leadership styles of Caesar and Jesus. Caesar is about peace through violence, greed, power-over, oppression. Jesus was about peace through non-violence, power-with, freedom, and all of this through a connection with God.

So, what was Israel longing for when Jesus was born? What was Israel longing for in the 8th and 9th decades when the birth narratives were written (not long after the fall of the temple in Jerusalem)? The same things we’re longing for now.

Borg and Crossan share a passage from the Jewish Sibylline Oracles, a fictional prophecy contemporary to the time of Jesus’ birth:

The earth will belong equally to all, undivided by walls or fences. It will then bear more abundant fruits spontaneously. Lives will be in common and wealth will have no division. For there will be no poor man there, no rich, and no tyrant, no slave. Further, no one will be either great or small anymore. No kings, no leaders. All will be on a par together. (p. 69)

There was a deep longing in the world then for peace and equality and living in harmony. There is still a deep longing for these things. For the author of the gospels, Jesus was the answer to that longing, he was the Messiah, the one who would usher in a new era of peace.

I’m afraid we’re not quite so naïve as all that. Yet, every Christmas we find renewed hope in the birth stories because Jesus still leads us back to God, compassion, spiritual connection, and caring for one another. He calls us to a deeper truth inside of ourselves, an inner wholeness from which we can draw strength for the work of wholeness on a larger scale.

For me, one of the biggest fallacies the church has perpetuated was that Jesus’ goal was for each of us to get to heaven. In my opinion, the path he set forth was never about a heavenly afterlife, it was a path (albeit a difficult one) to heaven – a place of peace and justice – here on earth.

What we long for and what we hope for, may we also seek and act for.

Advent blessings,

Kaye

*Photo Source: Sehnsucht (c. 1900). Heinrich Vogeler / Wikimedia Commons